Note: I am quickly writing this post at the end of J-term, so it will not be as in-depth or well written as past posts until I have time to re-write it

A year or two ago I wanted to make a wrist mounted computer (inspired by Fallout 3’s Pip-Boy 3000) out of a Raspberry Pi, which I didn’t have enough experience for. I haven’t worked on it since, but over J-term I made a usable mouse that I can adapt in the future to finish it.

Controls and Balancing Complexity

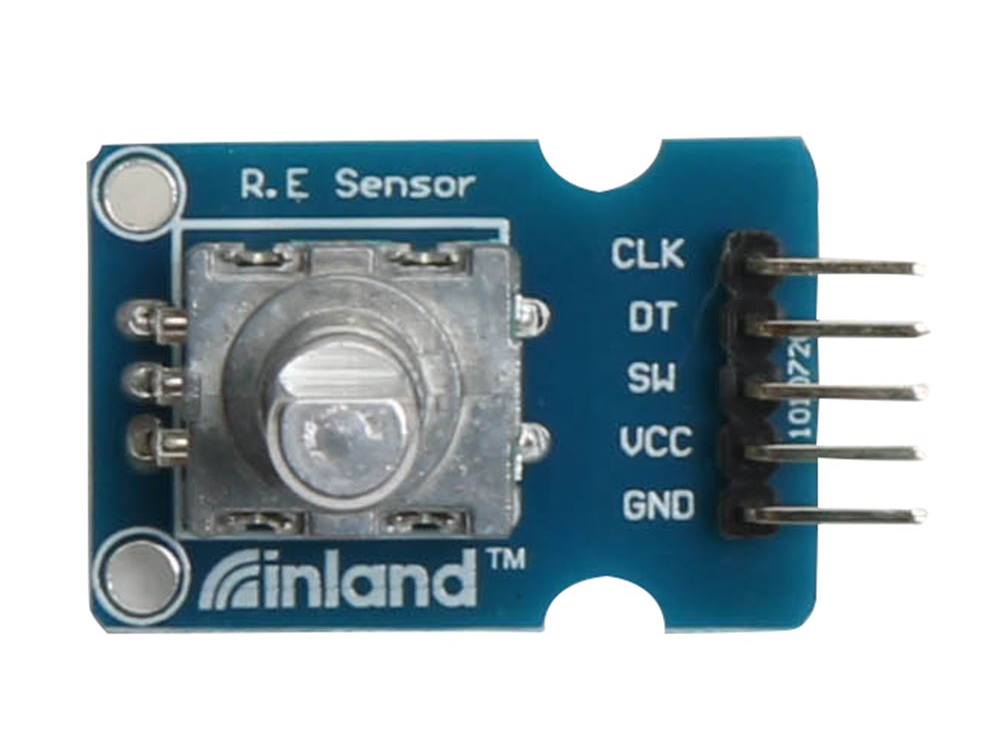

Before doing any concrete work, I was already thinking of how to incorporate mouse control without a mouse. Trackpads and ball-based mice would work, but I wanted individual control of the X and Y to be more interesting and have use-cases where it would be more helpful than a traditional mouse. I considered using a button for both X, Y, and scroll directions but that would be unwieldly and annoying to actually use. I decided on using rotary button encoders, which would combine the positive and negative directions of each axis plus a mouse button into a single module.

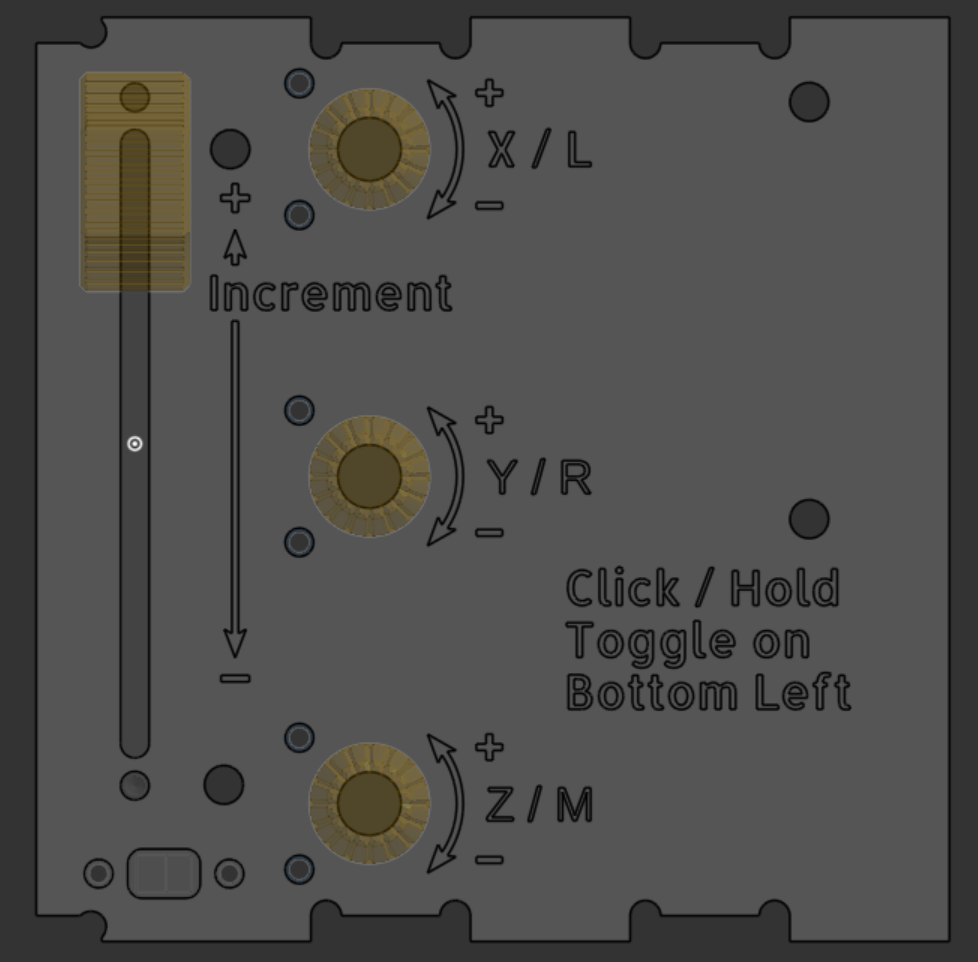

Two considerations to be had with any sort of mouse control are the sensitivity of the controls and how to handle holding down mouse buttons. I wanted to have my mouse be precise not only in moving axis, but also how far the cursor moved. On the other hand, I wanted to be able to use it as an actual mouse and not need hundreds of revolutions to cross the screen. My solution to this was to add a sensitivity slider controlling the movement resulting from each step of the encoders, allowing quick adjustments without needing to make multiple preset sensitivities and dealing with switching between them. As for holding down the buttons as opposed to sending a single click signal, I decided to add a switch that changed the button inbuilt into every encoder from a click mode to a toggle press/release mode. Alternatively, I could have added extra buttons to send the hold-release inputs or simply have holding down and releasing the encoder buttons do that like conventional mouses do. The switch that I added serves as a middle ground between these other options, adding some complexity to the hardware and software rather than thrice the number of inputs or double the code complexity. Additionally, removing the need to hold down the encoders’ buttons allows it to be easily turned without risking accidentally releasing the button, adding to its precision.

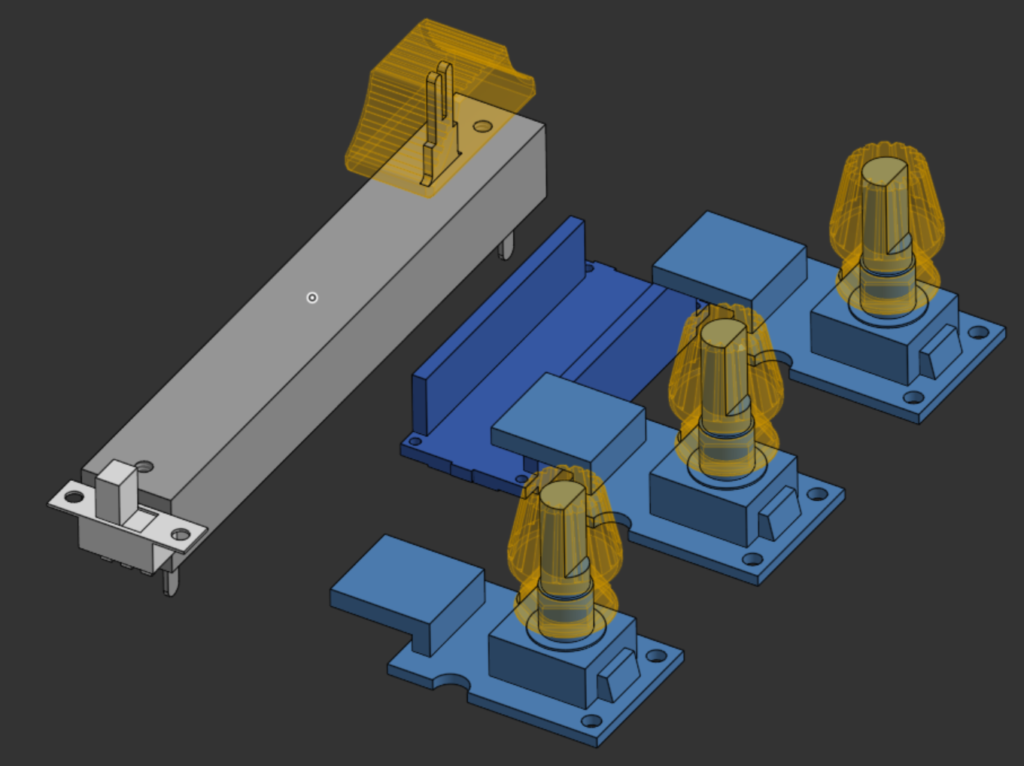

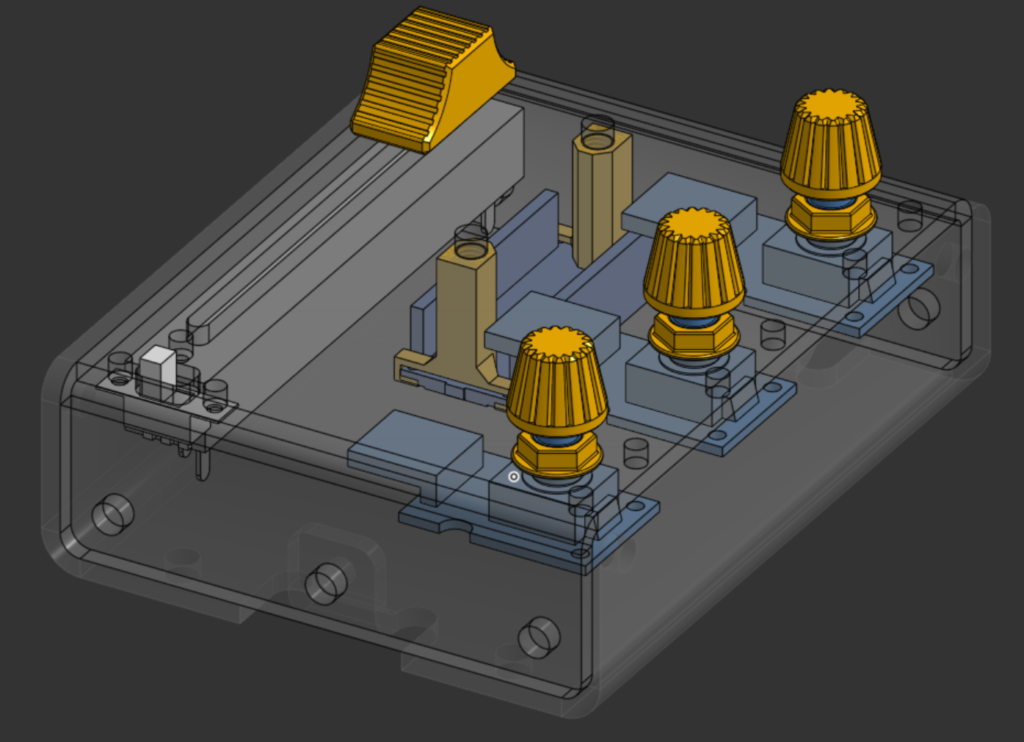

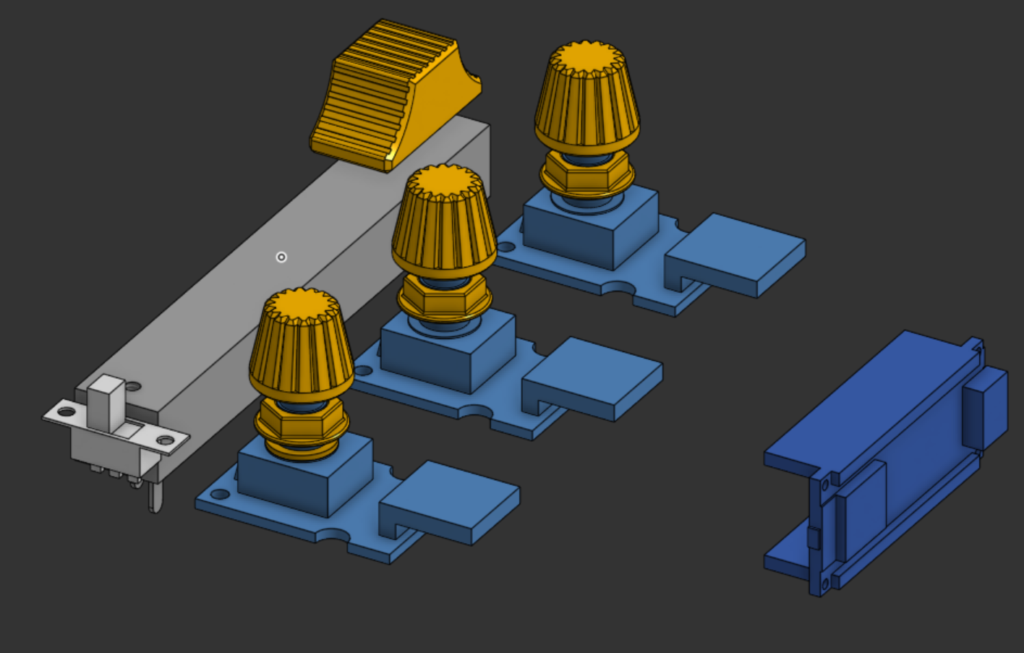

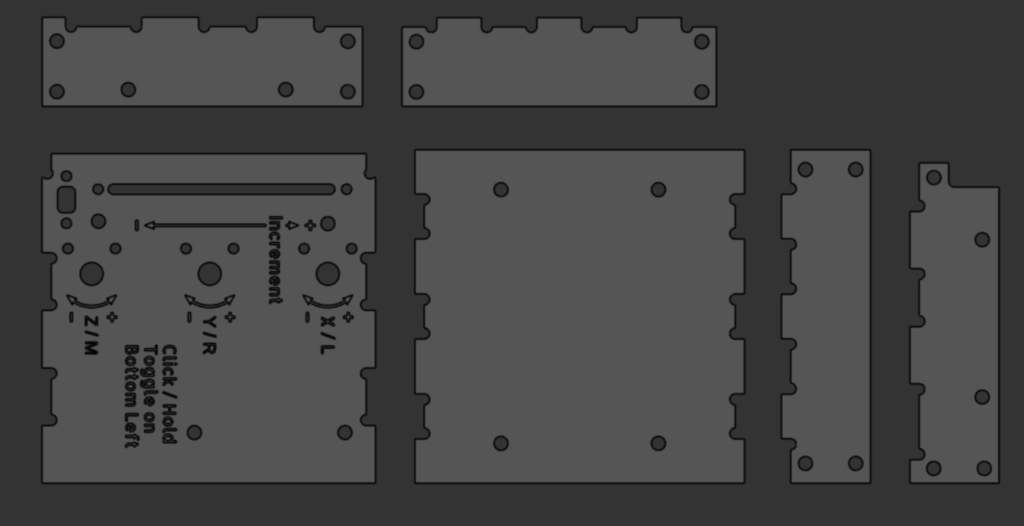

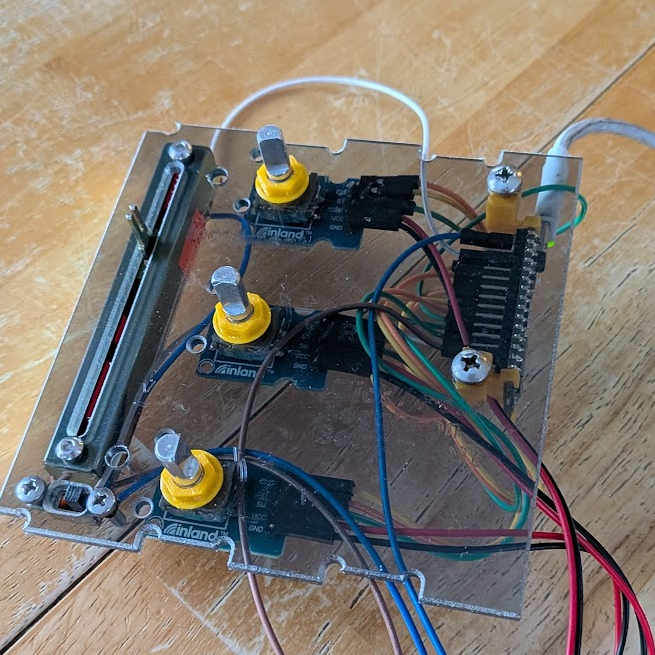

Below is the model for the top plate of the case, which shows the mapping that I used (besides for the X axis, which I should have inverted). The top encoder moves the X axis in the positive and negative directions based on how it’s turned, as well as sending a left-mouse-button signal that the switch in the bottom left turns into either toggling holding/releasing left click or a single left click. The other encoders act the same, controlling the Y axis and right mouse button and the scroll/Z axis and middle mouse button. Lastly, the increment slider determines how much the cursor moves down to (assumedly) the pixel. How the controls are arranged is based on what I found intuitive to control with one or both hands.

Working on Wiring and Code

(Link to the final code if you’re curious)

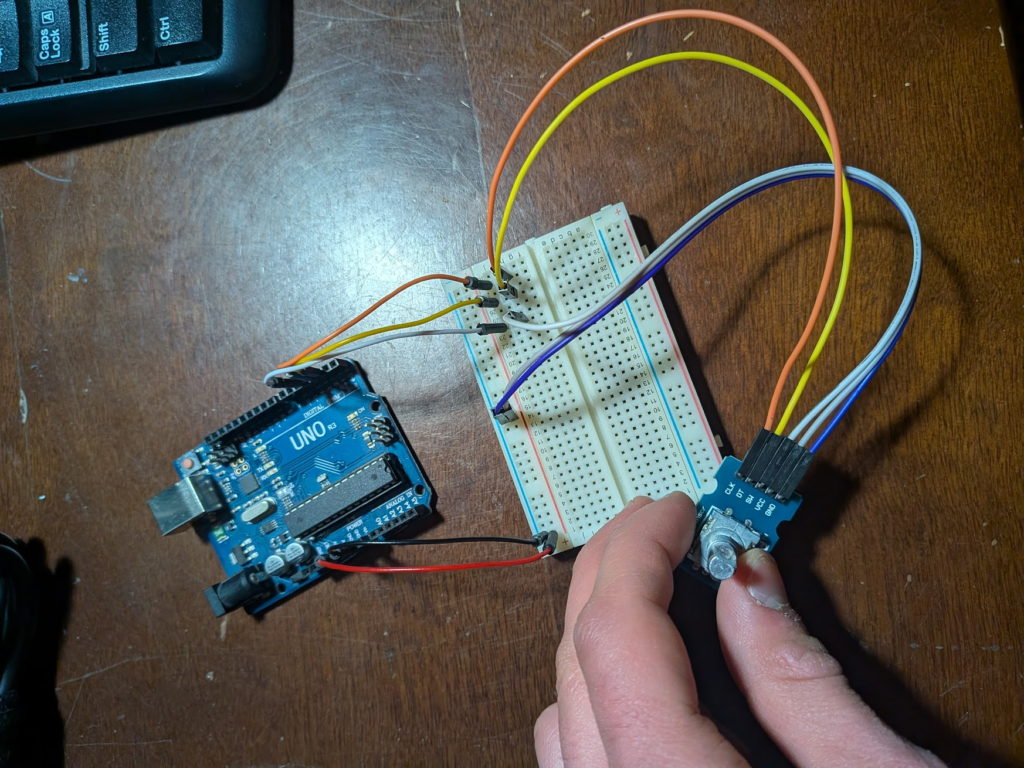

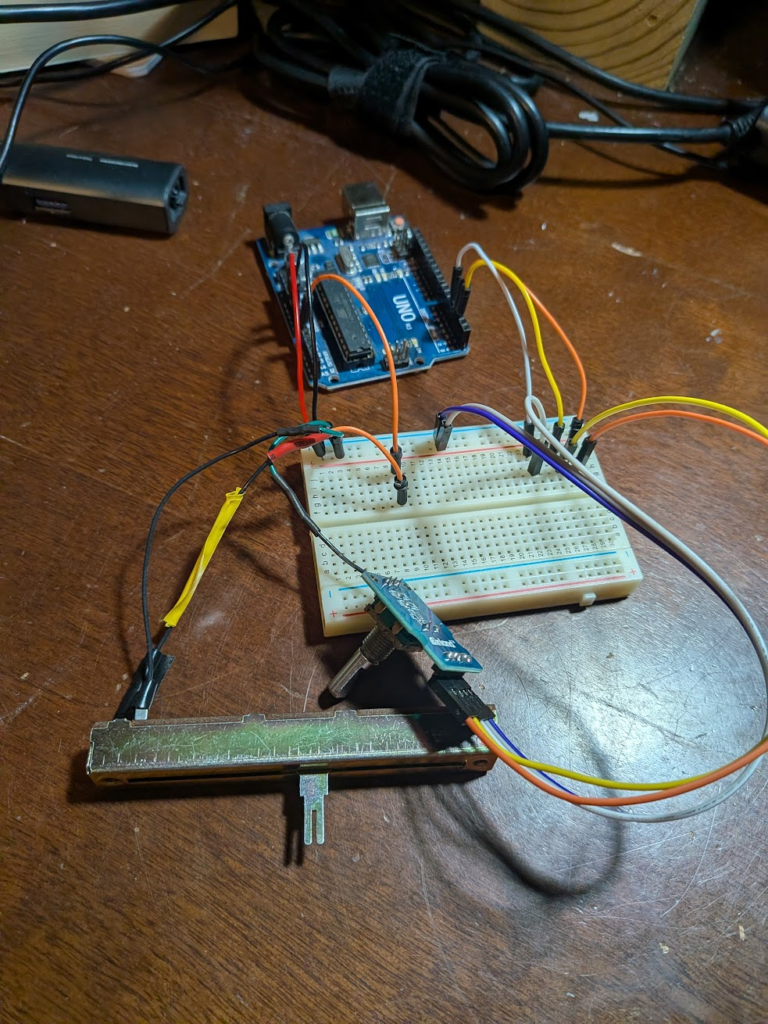

My first step, once I knew I would be using rotary encoders and a slider, was to get the rotary encoders working before I got my hopes up. I started with just one encoder hooked up to an Arduino Uno and used Arduino IDE to read its states. my original setup had LEDs to show whether the change in the encoder was positive or negative, but for simplicity (and having not taken a picture of it) I recreated the gist of it below.

I started by polling the state of the encoder’s clock and data pins after learning how rotary encoders work through Arduino’s documentation. The idea with this code and the rest I’ve written was that turning the encoder would brush contacts against an internal plate, and the order that contact is made is different in either direction. The clock state being high means that the encoder turned, and the data state tells the direction; if it made contact before the clock it’ll be off and that means the encoder turned one direction, and if it made contact after it’ll be on and that means the encoder turned the other way. I was having issues with this code where the output was essentially random, which I tried to fix with delays and using an if/else statement instead of an if statement for both data states. Switching up which pin was used as the indicator of movement and indicator of direction didn’t held, and neither did having both pins act as indicators of movement and direction. My best guess for why – as someone who has no code or Arduino experience – is that I could turn the encoder in the middle of the polling, which would either send a false input or none. I don’t have any code to account for that, so I tried another method.

void loop() {

digitalWrite(ccwLED, LOW);

digitalWrite(cwLED, LOW);

int xClkState = digitalRead(xClk);

int xDtState = digitalRead(xDt);

if(xClkState != priorXClkState && xClkState == HIGH){

//delay(5);

if(xDtState == HIGH){

digitalWrite(cwLED, HIGH);

cwCount++;

}

if(xDtState == LOW){

digitalWrite(ccwLED, HIGH);

ccwCount++;

}

}

priorXClkState = xClkState;

Serial.print("CW Pulses:");

Serial.println(cwCount);

Serial.print("CCW Pulses:");

Serial.println(ccwCount);

delay(0);

}Looking more into the capabilities of the Arduino Uno and methods for reading encoders, I tried using interrupt routines to get better results. I still had the same issue, so I tried using some libraries like MatHertel’s RotaryEncoder and StutchBury’s EncoderButton, but also had little success. Something was causing the encoder to randomly jump around in value, and sometimes trigger in the wrong direction. EncoderButton worked pretty consistently, but I disliked it since I would get two opposite signals when I tried to use only one interrupt pin or none. The Uno only has two interrupt capable pins and at this point I needed six, so I wanted a library that didn’t rely on them.

At some point in this search for a library I took a break to work on the slider using the Map function I learned a bit about in my Intro to ME class. Actually reading the slider was pretty simple and seemed easy to incorporate later, but I would run into some difficulty using it. For now though, I used an analog pin to read the value of the slider that I mapped into a multiplier later applied the change in X, Y, and Scroll, but for now just printed as a check.

const int pinSlide = A0;

void setup() {

Serial.begin(9600);

while (!Serial);

}

void loop() {

int slideValue = map(analogRead(pinSlide), 0, 1023, 1, 2400);

Serial.println(slideValue);

delay(100);

}

A week messing with libraries and being generally clueless frustrated me, so I took a hiatus until the last two weeks of break and got back to work. I had noticed earlier that a lot of the encoder libraries for Arduino reference Paul Stroffregen’s Encoder, so I decided to check it out. He has options for using polling rather than interrupts, and I got good results aside from whatever input being quadrupled when outputted. I tried to divide the output by four, but that didn’t solve the problem on its own due to (I think) my use of an integer not allowing fractions. Combining that with the use of a remainder in the if condition, which I found (but can’t re-find) in the library’s issues page on Github, only one output is sent that is the encoder’s change in position multiplied by four but divided by four. I’d read the library’s documentation for why there are four signals, as I’m not entirely sure myself. After getting that sorted out, I added the slider value as a multiplier.

I had to change the mapped values for the slider for a couple reasons. The direct analog output from it was originally 0 to 1023 at 5V, but I had to change it’s input power to 3.3V as I needed to switch to a specific model of Arduino Nano to emulate a mouse. As for the mapped range, I ran into the issue where a higher value than 120 as the multiplier would actually decrease the increment that the cursor moved, then go into the opposite direction. With a really large range, moving the slider up slowly made the multiplier into a sine function that kept reversing the multiplier. I think this is because my xChange variable was defined as int and not long, but 120 pixels per change in position was a good enough increment for me so I just capped it there.

//in void().loop

Mouse.move(xChange, yChange, zChange);

xChange = 0;

long increment = map(analogRead(slider), 0, 4095, 1, 120);

long xNew = encX.read();

if (xNew != xPos) {

if (xNew % 4 == 0) {

xChange = -(xNew - xPos) * increment/4;

Serial.print("xChange: ");

Serial.println(xChange);

xPos = xNew;

}

}With one encoder working and especially alongside the slider, I copied the above code and changed the variables to Y and Z. I also added the button functionality with Ardunino’s ezButton, then added the switch functionality. The code below, which I copied for the Y and M buttons, just reads if the button is pressed using the library and checks the state of the switch. If it’s off the mouse is clicked and the the left mouse button is released if it was previously held. If the switch is on, it checks the lState variable to determine if it is actively being held. If it isn’t it will start send a start-holding-down signal and set lState to 1 (on), and if it is being held it will send a stop-holding-down signal and set lState to 0 (off).

//in void().loop

int toggle = digitalRead(togglePin);

buttonL.begin

if(buttonL.isPressed()){

if(toggle == HIGH && lState == 0){

Serial.println("l click toggle on");

lState = 1;

Mouse.press(MOUSE_LEFT);

}else if(toggle == HIGH && lState == 1){

Serial.println("l click toggle off");

lState = 0;

Mouse.release(MOUSE_LEFT);

}else if(toggle != HIGH){

Serial.println("L Click");

lState = 0;

Mouse.click(MOUSE_LEFT);

}

}

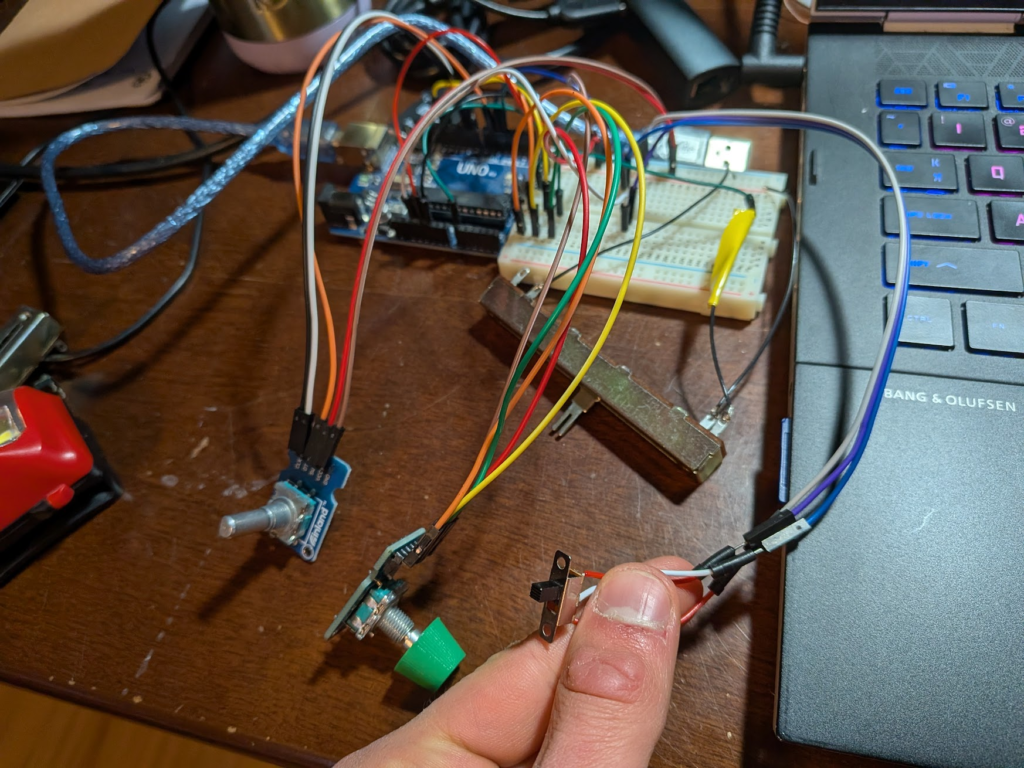

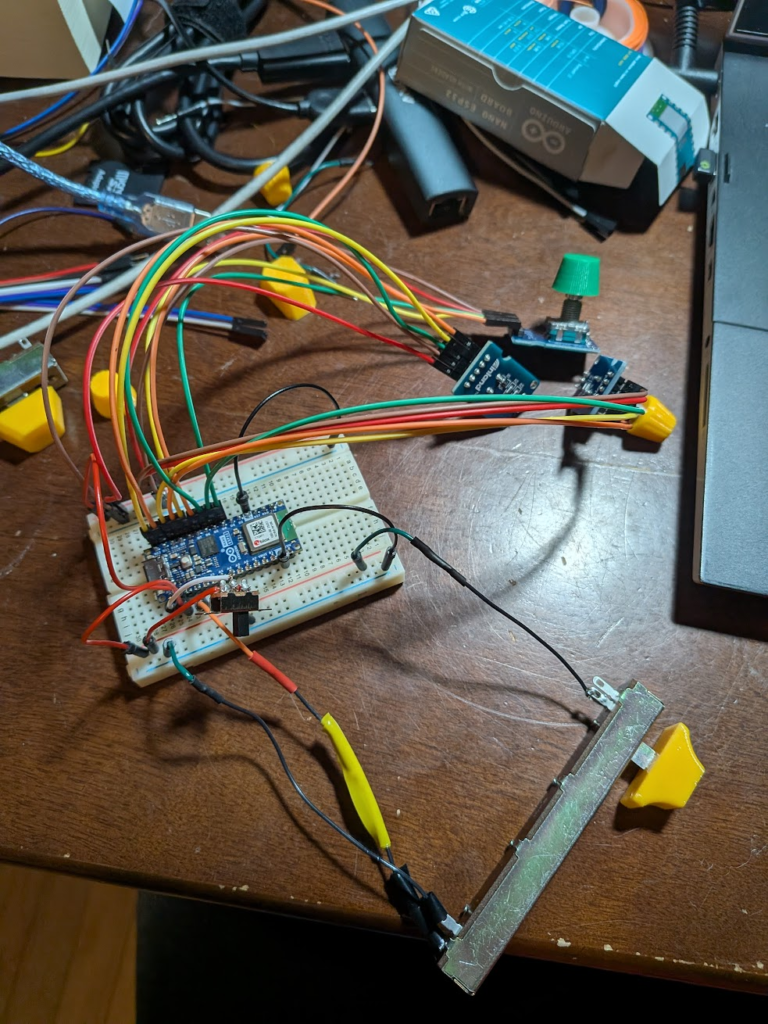

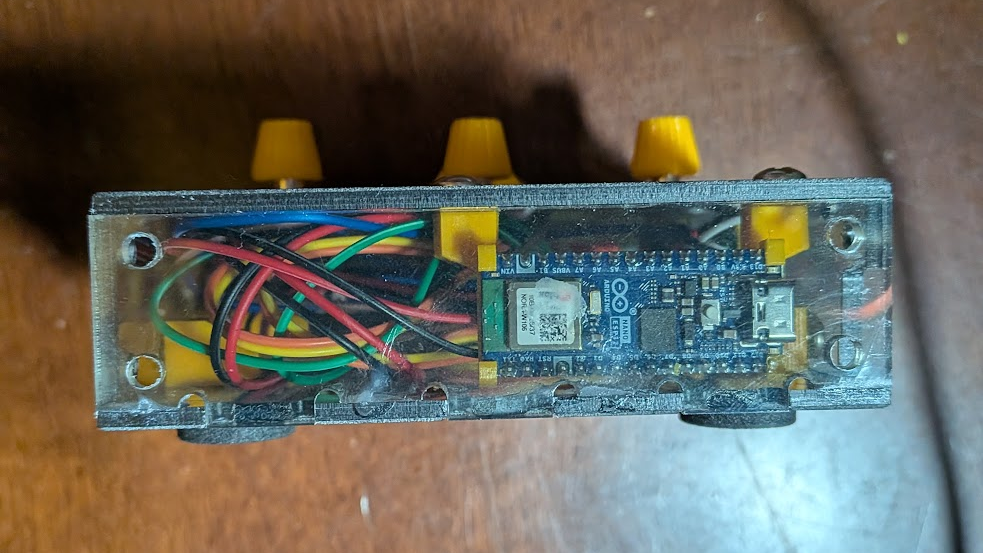

As I mentioned earlier, I had to switch from an Uno to a Nano. The Uno, or at least the version I had, doesn’t have USB HID communication. Some quick research showed that an Arduino Nano ESP 32 was capable of it, and so I had to grab one from microcenter. Switching over to the Nano was an easy process, although I had to make sure that it only was sent 3.3V signals and that everything code-wise still worked as intended. I had to use a couple more built in Arduino libraries, then was able to test the mouse as an actual mouse. After a couple small changes, I was ready to start making a case to make it easily usable.

Making the Case, Assembly, Final Wiring

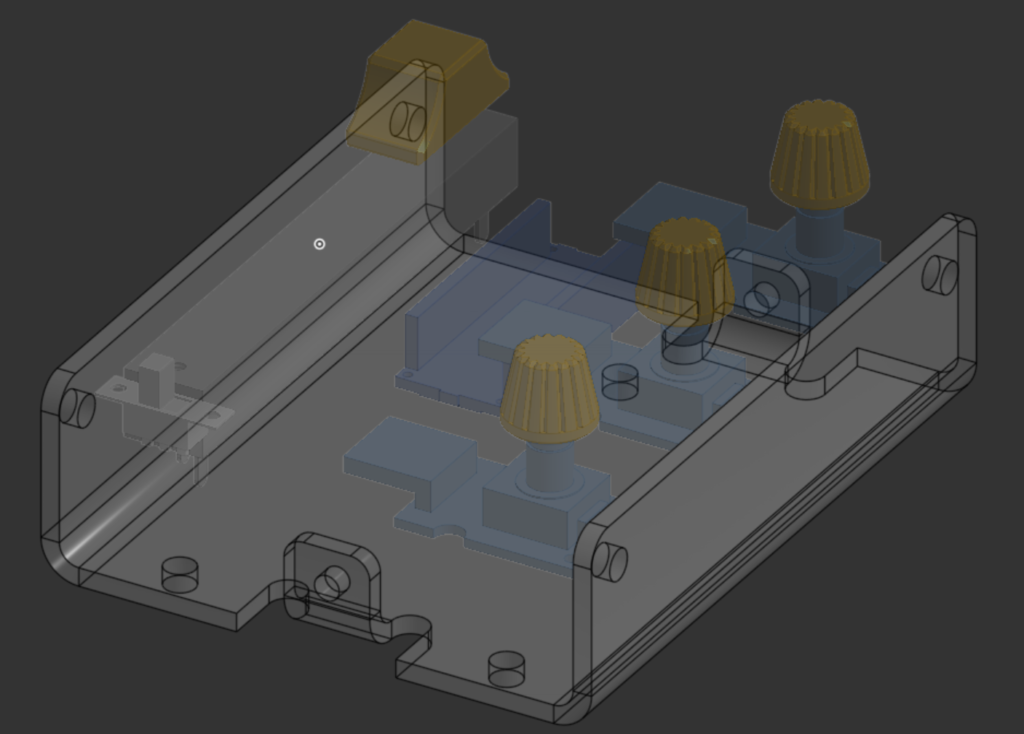

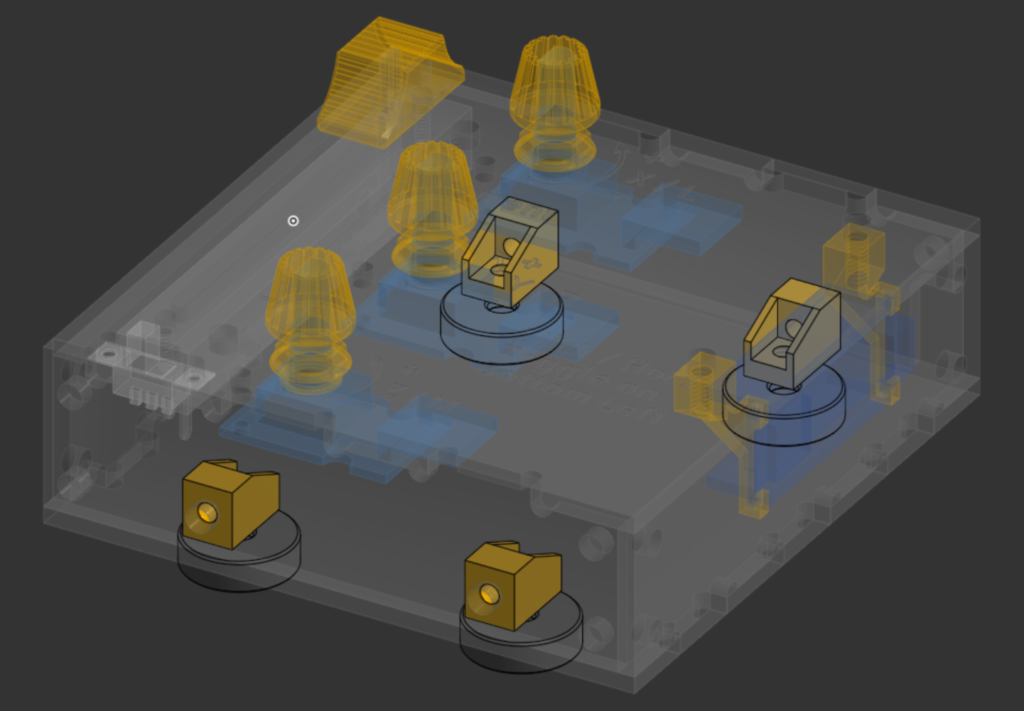

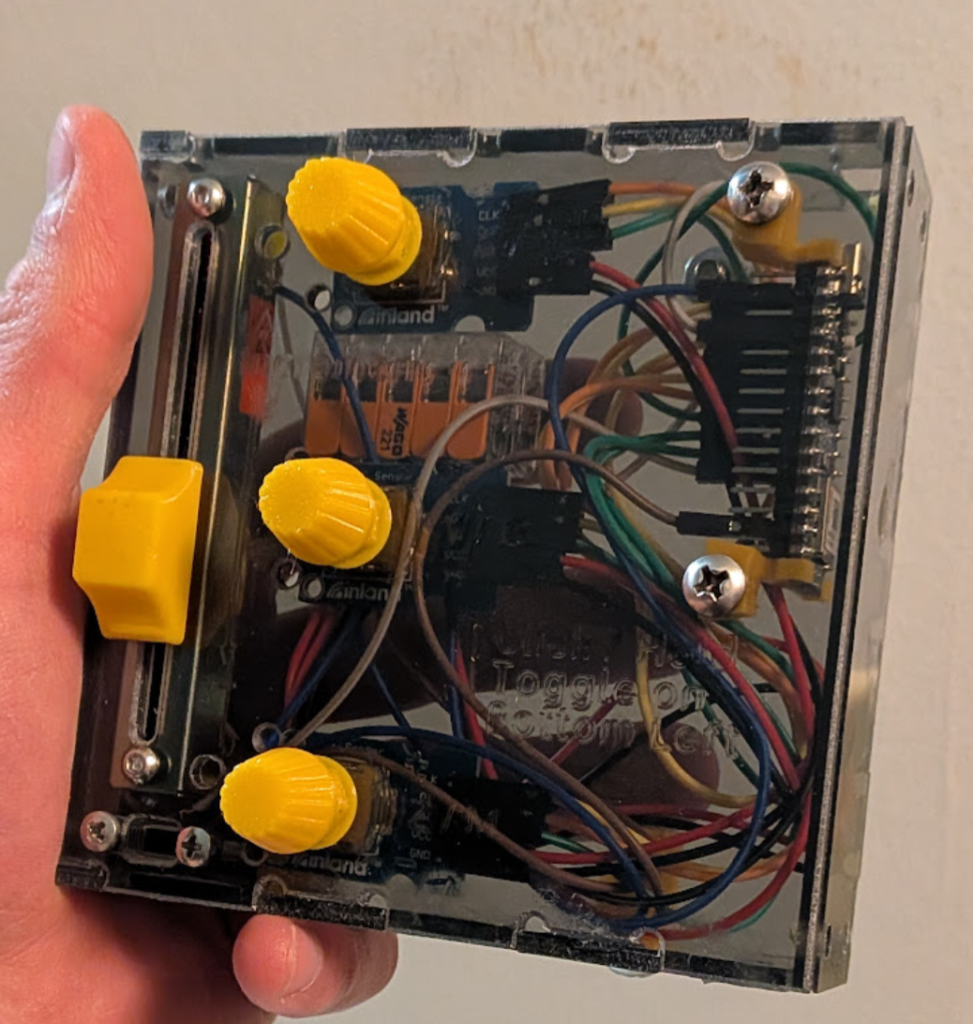

To start making a case for the mouse, I modeled all of the electrical components and arranged them in a layout that worked for me. I also modeled caps for the components that I would be grabbing to make them more ergonomic.

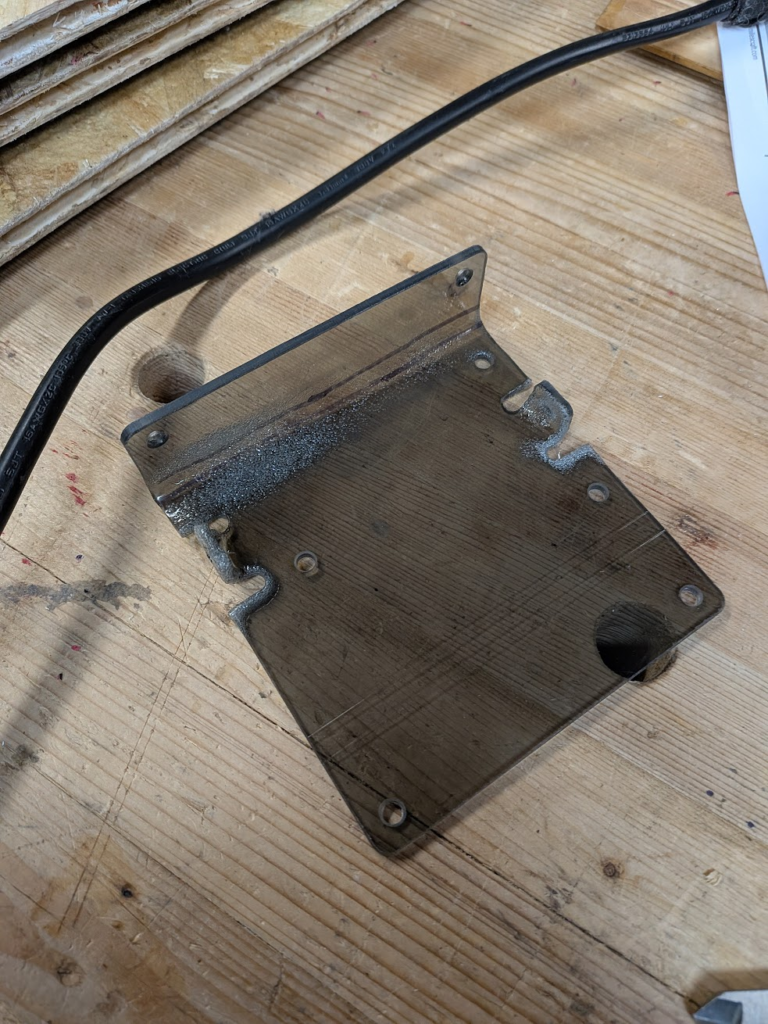

Using the layout as a guide, I modeled a case that was two bent polycarbonate parts. My hope was that I could bend them cleanly, but with an impromptu heat gun and angle iron setup I messed up horribly.

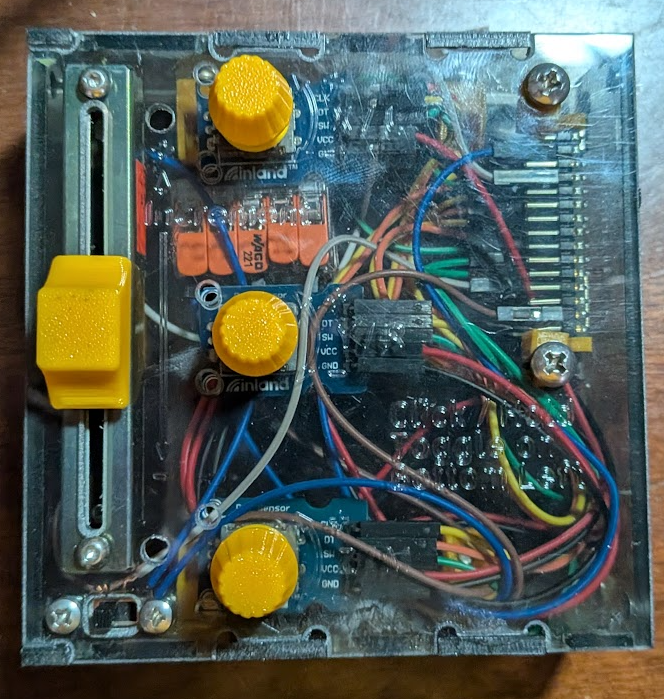

Another issue I ran into besides failing to bend the plastic was that I did not have enough room for wiring. I planned on using jumper wires so that I wouldn’t have to risk damaging the Arduino or rotary encoders by soldering them, and that was just not possible. Redesigning the case, I changed my layout to include more of room for wiring and to align the Arduino’s pins with the pins of the encoders.

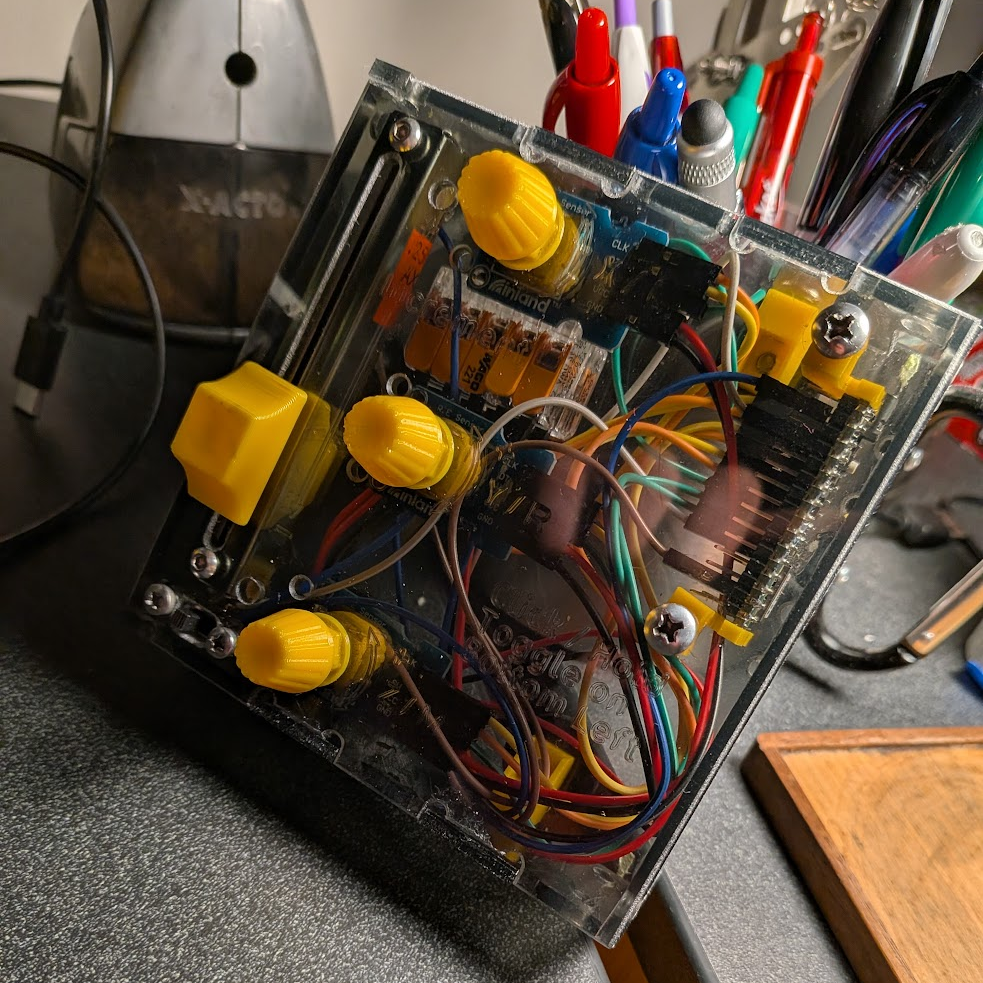

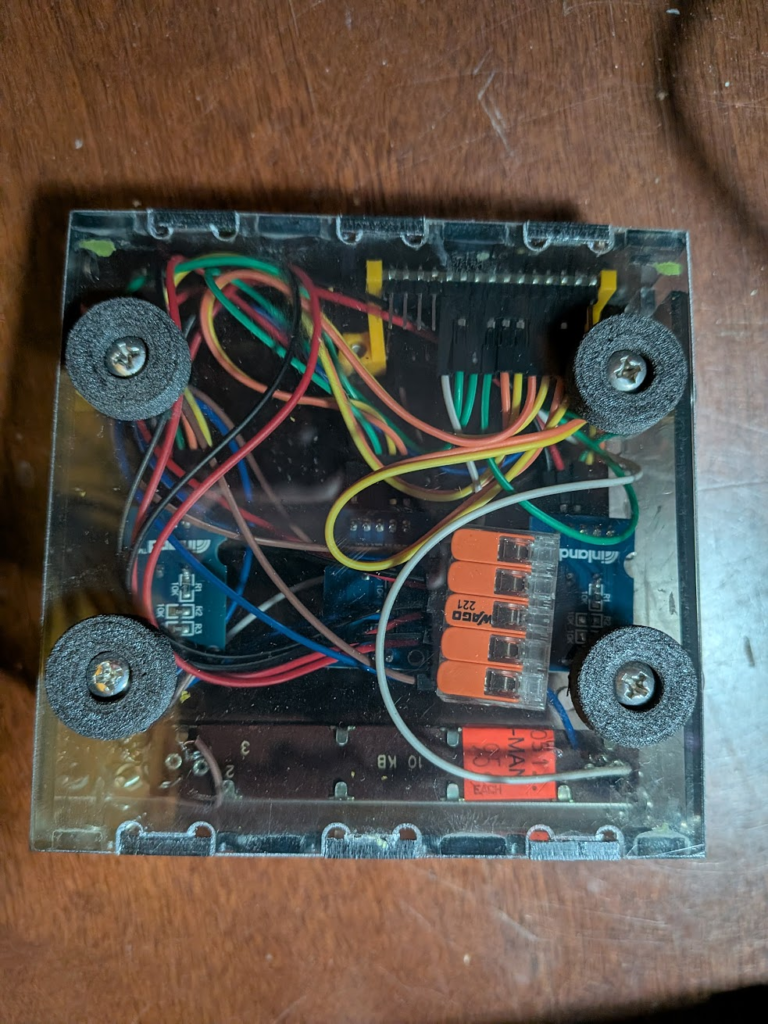

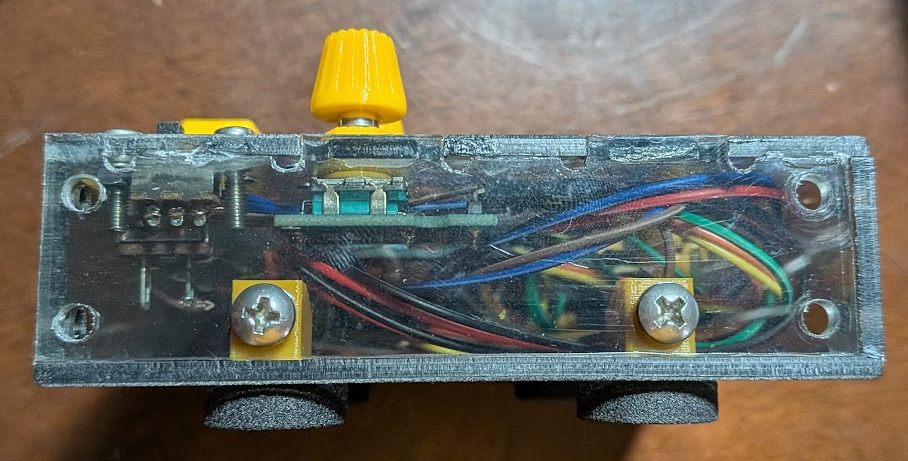

As for the case, I redesigned it to be put made of easily to align joints that I could glue together. The top plate would be glued to the front and back, while the bottom was to be glued to the side plates. I’d put the two pieces together using brackets I’d screw into, which I also used as attachment points for TPU feet for stability and to protect whatever the mouse is set onto.

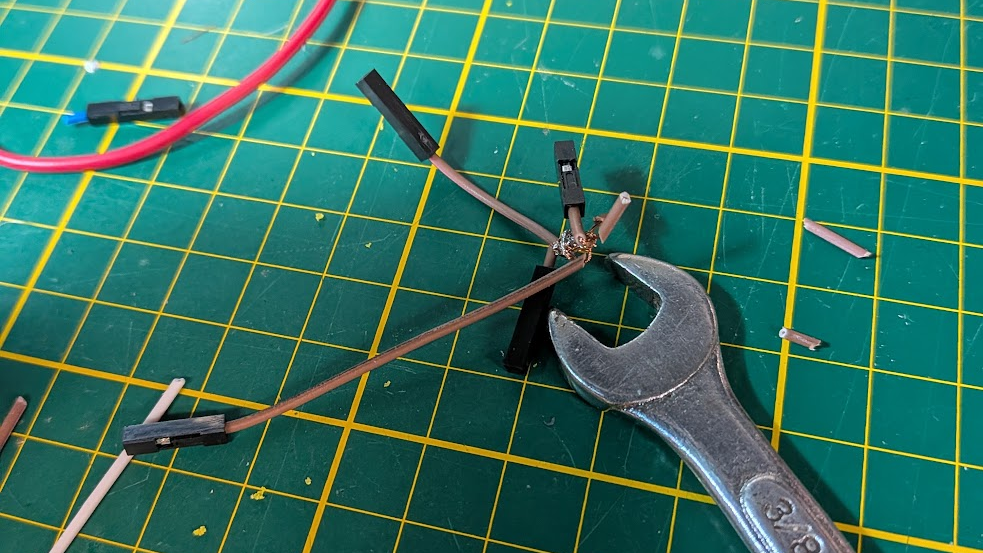

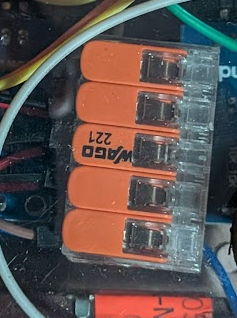

As I glued the bottom part of the case together, I attached all of the electronics to the top plate and worked on final wiring. Initially I tried to use splice the end of leads together to form one big ground chain, but I cut the wires too long and it just worked out poorly. The Arduino Nano only has one 3.3V output and two grounds which meant I had to have some sort of power/ground chain, which I eventually did using WAGO connectors and male to female leads. There were 5 slots in the largest one I had and 6 components to connect, so I chained the power and ground for the slider off my switch. There weren’t any leads or pins attached to them already, so since I already had to solder on them this worked out well.

The wiring doesn’t look pretty, but it’s good enough for me. I had to take all of the components off of the plate to glue the top part of the case together, but before I did that I made sure to test that everything was wired correctly before I made it more difficult for myself.

The last thing I did before fully assembling the mouse was to get the protective feet printed off. I tried out a filament called TPU Air from Siraya Tech that has a different durometer depending on how how you print it, printing off 60A, 65A, and 70A (left to right) feet to gauge how soft I wanted them to be. I liked the 65A the most, so I went with that.

When I finally assembled the whole mouse, I didn’t have any dedicated wire routing and just shoved the WAGOs and wires where they would fit, which isn’t a great solution but one that works.

What I Learned

I haven’t done much wiring and designing for electronics before this project, so it was helpful to be burned by poor layout and not having enough space. In the future I’ll definitely try to give myself extra wire and wiggle room, and maybe even plan out routing before going all in. Likewise, I hadn’t written any code and got some practice researching how to get results, as well as some trial and error.

Link to CAD: EaS Mouse

Link to Final Code: https://johnsonspot.com/etch-a-sketch-mouse-code/

Photo Gallery

I love the look of this project, so here are some pictures with difference angles. There’s some smeared and dried glue that I might try to remove in the future, but for now I’ll just live with it.

Leave a Reply